Japanese school lunch is often the envy of the world, considered the epitome of nutritious school lunches and a school lunch system done right.

Having the opportunity to teach at an elementary school in Tokyo, I was lucky to experience the Japanese school lunch system over an entire year. School lunch in Japan or kyūshoku (給食, きゅうしょく), as it is called in Japanese, is extremely convenient, not to mention very affordable.

Parents can expect to pay around 250 yen (US$2.50) per day for kinder and elementary school students, and anywhere from around 300-450 yen ($3-$4.50) for junior high and high school.

So, just what are Japanese school lunches all about and how does it all work?

Table of Contents

School lunches in Japan

Often when many of us think of school lunch, we imagine soggy and tasteless bain-marie food served cafeteria-style, designed to fill bellies rather than constitute a healthy diet. Japanese school lunches, however, are carefully planned and do not include any of the “fast food” options that we might stereotypically associate with school lunches. School lunch menus are usually planned by a nutritionist and made on site, and much attention is paid to the nutritional value and balance of the meals.

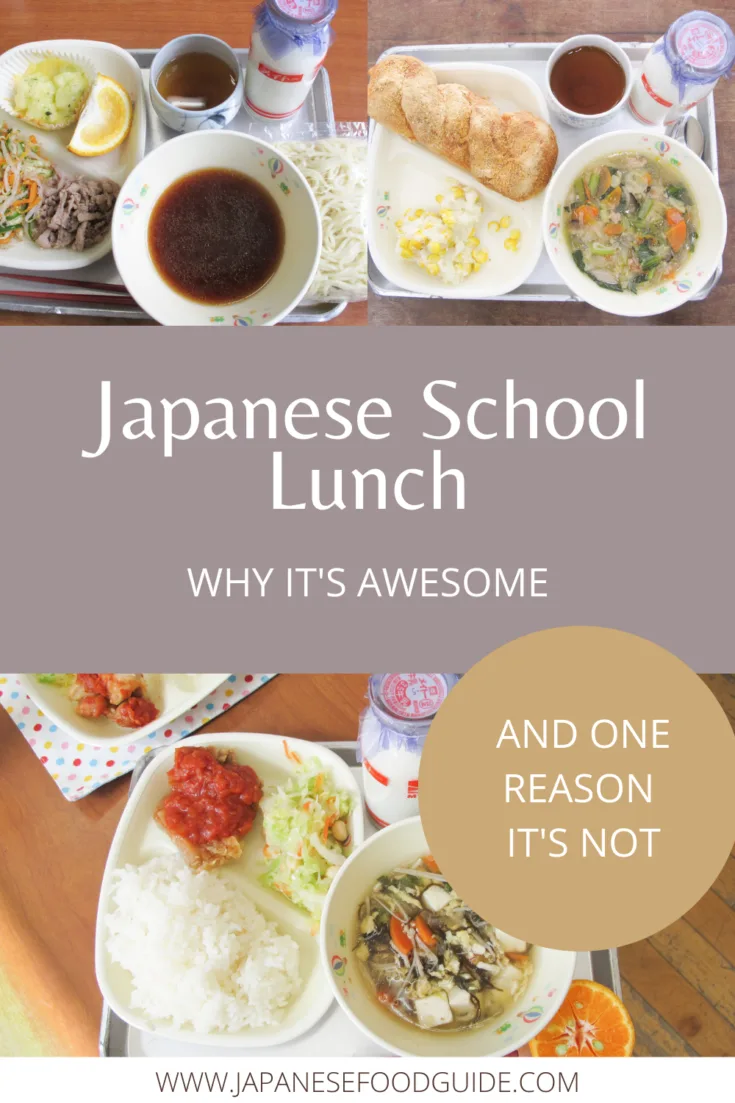

At my school, common meals included vegetable- and tofu-laden soups, noodles, rice, salads and vegetable sides, fish, meat, curry and other sauce-based toppings, fruit, tea and a bottle of milk. There was typically always fruit, a hot cup of tea (like green or roasted green tea – hōjicha) and cold milk in a glass bottle.

And despite the menu often featuring the same types of dishes, I don’t recall ever getting the exact same meal twice. We often had soup, but with so many types of bases and vegetables to choose from, it always felt different and varied. The salads and vegetables were very seasonal and always put together in a creative way so that it never got repetitive. The servings were plentiful and I sometimes found it difficult to eat it all and quickly. My students often asking me, “Why do you eat so slow?”

Here are some examples of school lunch in Japan.

School lunch team

School lunch in Japan is served by the students. Yes, even by the first graders! Each class will have an assigned group of students in charge of collecting the meal, serving it, and then taking the dirty dishes back.

Students take a lot of pride in being on school lunch duty and often really look forward to their turn. They get to be in charge and show how capable they are in front of their teacher and fellow students.

The first part of that duty is to collect the food, crockery and eating utensils from the kitchen. At the school I worked at, these were large metal trolleys. Often with a large vat of soup, rice, all the sides and serving dishes, not to mention about thirty full glass milk bottles, they would be quite heavy and difficult to maneuver.

One of my all time favorite memories of this time was seeing gaggles of first graders trying to push the trolley to their classroom each day. There were six of them for each class trying to push but they could never get it to go in a straight line. The trolley would skew in the direction of the wall. Then they’d re-calibrate and push again, this time going towards the other wall. And down the hall they would go in a zig-zag pattern, all the while discussing their strategy. I’m sitting here smiling as I type just thinking about it.

I really wanted to help them but had been specifically told that we weren’t to do that. Getting the lunch to the classroom was all part of the learning – developing their problem-solving skills, spatial awareness, team-building, as well as their physical capabilities.

Instead I would wish them luck as I walked past and they’d always reply with the utmost seriousness that they would do their absolute best and get the job done. It was really quite wonderful watching their concentration and their trolley pushing go from complete chaos the first few months of the school year to increasingly coordinated.

First grade classrooms were always the closest to the kitchens for this reason, and the six grade classrooms the farthest away, so that each year as they got more coordinated and confident, they could push themselves (and those trolleys) a little further.

Logistics and Getting ready for lunch

Japanese school lunches are generally served in homerooms, rather than in a cafeteria-style space. Firstly, many schools may not have a large enough and appropriate lunch-serving space to accommodate all students, and the way that school lunches are organized in Japan would mean that it would be very difficult for students of each level to get the trolleys to and from the kitchen. I can’t imagine how much time it would take!

When the students are responsible for the serving and cleaning up, having a contained space with just the class makes sense. Things can get done a lot faster, it’s easier to supervise and instructions can be heard easily, and the class can start eating when they are ready, rather than waiting for any classes that may be lagging. This is important to mention because in Japan it’s customary to wait until everyone has their meal in front of them before anyone starts eating.

While the food is being fetched by the school lunch team, the other students are prepping themselves and their classroom. They would be put into small groups so they could eat together in a more social setting than the usual classroom set-up of individual desks all facing the black board. They’d put their desks together, wipe them down, and then put down their cloth placemats and small towels/washcloths/napkins they’d bring from home.

They’d also put on their white school lunch jackets (a bit like a smock) to protect their clothes, and don white hats to keep their hair out of the way and cloth face masks for hygiene. Of course, each student would wash their hands thoroughly before the meal. There was a sink in every classroom for this purpose. This is another reason why students bring their own washcloths – to dry their hands. The school lunch team would already have washed their hands and put on their lunch outfits before leaving for the kitchen.

Serving Japanese school lunches

When the school lunch team arrives back, they will start serving the meal to their classmates. The students learn to serve and carefully handle hot soup and other hot dishes, portion control and how to manage time and gets things done efficiently. Everyone is hungry, including those serving, so the students need to work collaboratively so that the meal can start as soon as possible.

The students are also responsible for serving their teacher. Unlike the students, who are expected to line up and get their food from their classmates, the school lunch team must bring the homeroom teacher their meal at their desk.

As I was the English teacher and would teach many different classes each day, I would go to a different class each lunch time. The students would assign me a table after they played rock, paper, scissors, and upon arrival at their classroom (after being collected from the staff room by two of the lunch duty students) would tell me which group won and accordingly where I should sit that day.

A desk would have already been cleared and placed there for me and the students would bring my meal to me. I tried going to get it myself at first, but the students wouldn’t allow it. There are set rules to be followed and they get vocal if you don’t do it right!

In fact, while the homeroom teacher is present during lunch and eats with the students, the whole Japanese school lunch system is essentially entirely student led, and they take the running of it very seriously. The teacher doesn’t really intervene because they don’t have to.

The students all know the drill and everyone is expected to do as they are told by the school lunch team. It doesn’t matter if they were classmates a few minutes earlier, they have the authority now and everyone respects it. Nobody would think it was funny if they didn’t because it delays eating, and then the subsequent playing outside for the rest of lunch.

If anyone is dawdling or talking when the school lunch team is addressing the class, expect other students to instantly reprimand that student and for them to quickly fall into line.

School Lunch Menu

At my school, once everyone was seated with their meal, there was one more item of business before eating, and that was the announcement of the day’s menu.

One or two members of the school lunch team would take the menu, that had been posted on the wall by the door since morning, and read not only what we’d be eating that day, but where it came from, and the nutritional value of each item, and total caloric intake. “Today we are eating grapes from Yamanashi Prefecture.” “These mountain vegetables were all picked within 2km of the school.”

On special days, our meal would reflect that event. For example, on Tanabata (the Star Festival) our soup contained okra, as when it is cut it looks like little stars, and along with the thin sōmen noodles, it supposedly represented the Milky Way, which is part of the legend of the origin of Tanabata.

Sometimes there would even be a quiz and the students would raise their hands when they heard what they thought was the correct answer. Like, “What prefecture is famous for producing apples?” There would always be audible appreciation for foods that had come from places where they are a specialty. Over lunch the students would chat and say, “Aomori is famous for apples, and we get to eat them fresh for school lunch. How lucky are we!”

Then we’d all say itadakimasu in unison and could then begin our meal.

Learning to eat everything

While the meal is taking place in the classroom, it is part of their lunchtime and therefore break time. But it is also educational and a fun extension of the learning that happens during class, in a more practical application.

School lunch is a lively time, full of chatter and ravenous eating. Students are expected to eat everything on their plates, so they learn to eat lots of different things, even if there is something they don’t particularly like. And when I say they have to eat everything, I mean clean their plates. Once I had left a couple of grains of rice in my bowl, just because they were stuck and it can be hard to pick up those last few smushed grains. I’m talking 2-3 grains here. Well, you best believe those students wouldn’t take my dishes until I painstakingly maneuvered them to the lip of the bowl and finished them. They had no qualms at all in telling me so. I may have been in a position of authority in class that day, but during school lunch, the students run the show.

The students were shocked on my first day when I mentioned this was my first time to have school lunch. “Teacher, don’t you have school lunch in your country?” “No, we usually have to bring our own food from home or buy food from the canteen.” When I told them the usual foods that are available at the school tuck shop, they replied, “Gosh, how sad.” And when I mentioned that drinking plain milk in a bottle like this was also something new to me, they gave me a lecture about calcium!

Students love their milk

In fact, the only time I ever saw the students become disappointed during lunch was on a day when we had heavy snowfall and the truck could not get to the school to deliver the milk.

Such a staple and beloved part of their school lunch experience, this was basically the worst news ever, and there were even a few quiet tears. Telling them it was OK and that we could have water instead, really didn’t make them feel better, and was met with stares of, “You clearly don’t get it, do you?”

Even as I left the classroom and the kids were all scurrying in the halls to go play outside, they stopped to lament the fact that there was no milk that day. “Oh what a shame!” they exclaimed. Their appreciation for it next school lunch day was apparent and they all discussed how extra oishii (delicious) it was and thank goodness the snow had stopped.

I also came to appreciate the milk, from drinking it just because I had to, to actually looking forward to it. So I guess the Japanese school lunch system worked on me too. There was no room for pickiness. Everyone just got on with it and appreciated what they had on their plate.

Leftovers

Often there would be a little bit of food leftover and extra milk bottles, especially if there were absences that day, and any students who wanted more food or milk would play rock, paper, scissors to decide who would get it.

Someone from the school lunch team would announce what was left partway into the meal and supervise the game and distribution. This was all done very efficiently and the students always accepted the result.

This is also an exercise in understanding limits. As you have to eat everything you take, students learn to only put up their hand for more if they actually want to have more, and can finish it by the time everyone else is done with their lunch. They learn that if you over-eat, you don’t feel well and it’s difficult to run around and play with your friends after.

End of the meal

At the end of the meal, the school lunch team would again be taking control of proceedings and formally announce that lunch was over. On their count, everyone would say gochisousama deshita in appreciation.

Then there would be a flurry of activity, as all the dishes were expertly and neatly packed back onto the trolley, desks wiped down and moved back to their original positions. The school lunch team would then return the trolley to the kitchens, while the rest of the class started to get ready for playtime.

This involved not only removing their “eating clothes” but changing into their outdoor play uniform (which was different to the uniform they wore inside for class). This all happened in the classroom and in what felt like thirty seconds as they bounded out of class to enjoy the rest of their lunchtime in their shorts and t-shirts.

Snacks

I had always thought the school lunch serving sizes were really large. It might not be obvious from the photos, but the rice and other portions were quite substantial, and once you put all the bits and pieces together, it was a sizeable and filling meal for adults, let alone smaller children.

But I learned something that shocked me about food at elementary schools in Japan, and that is that snacks are generally not allowed, at all. The children are not permitted to bring snacks from home and they are not provided as part of kyūshoku once they hit elementary school. In fact, it’s common practice for the usual two snacks a day provided at hoikuen (Japanese pre-school) to be reduced to one at kindergarten to ready them for no snacks by the time they get to first grade. So at morning recess, elementary school children cannot eat anything and must wait for lunch.

It’s no wonder then that if they haven’t eaten since breakfast, they are really famished come lunchtime. I remember being starving at morning recess at that age – I don’t think I would have been able to concentrate if the same rules applied. But if your body is used to this schedule, like all things, it simply becomes the norm.

However, it does put into context why the students become very efficient at getting organized around school lunch and their no-nonsense attitude towards it starting as soon as possible. In retrospect, I should have taught them the word hangry, as that probably sums up exactly how they felt in the time between the end of fourth period and actually being able to take the first bite, or when the milk isn’t delivered that day!

Allergies and other special dietary requirements

One downfall of the Japanese school lunch system is that special dietary requirements are generally not catered for, and affected students need to bring a bento packed lunch every day instead (again no snacks allowed). This means if you have an allergy, are vegetarian or vegan, or cannot eat certain foods for cultural or religious reasons, you may not be able to participate in the school lunch program.

However, it isn’t quite as simple as bringing a bento in lieu of school lunch. Students with special dietary requirements generally must get permission to do so. If the reason is medical, as in the child has an allergy, parents will need to get a doctor to sign off on it and bring that paperwork to the school. Once all approved, they can then bring their own bento. The allergy test though must be conducted annually (via blood test), as it is quite common for children to grow out of some allergies. Therefore, students who started out taking bento may join their classmates in having school lunch in later years if it is no longer deemed medically necessary.

It does, however, depend on what the student is allergic to. Allergies to things like eggs, milk, soba (buckwheat) and shell fish usually mean no school lunch. But peanut allergies are generally considered OK as peanuts are not a typical component of traditional Japanese cuisine. And with no snacks, students are not eating biscuits, chocolates or other processed items that may contain traces of nuts. Severity of the allergy may also be considered. If the allergy is more of a mild intolerance, some schools may allow the student to have school lunch and avoid the ingredient in question.

If the special dietary requirement is for a non-medical reason, permission to take a bento must generally be signed off on by the Japanese Board of Education. This includes any families who are vegetarian or vegan, or cannot eat certain components typical in Japanese school lunch, such as pork, which in my experience was contained in most soups and some side dishes.

This lack of inclusivity is probably the one major aspect of Japanese school lunch that needs a massive overhaul.

Final thoughts about Japanese school lunch

Getting to experience Japanese school lunch first-hand was one of the most interesting parts of working at a Japanese elementary school. I learned a lot about the emphasis placed on collaboration and the collective culture, and it was truly incredible to witness just how seriously the students took school lunch responsibilities. The range of quality meals was impressive and school lunch was something I looked forward to because it tasted good.

The Japanese school lunch program varies from area to area and school to school. Many schools have lunch provided every day, some others have a mixed combination of bentos and school lunch, and some others may be bento only. At the school I worked at, there was school lunch three days a week and two days a week students would bring their own bento boxes from home. Fortunately for me, the two days a week I worked there were both school lunch days! It was a real blessing not to have to think about what to have for lunch that day and having to pack something early in the morning. And the fact that it was a hot nutritious meal.

Many of my parent friends really appreciate not having to do lunch prep, and really miss it during holidays or on bento days. While kyūshoku is standard for younger children (at both public and private) and public junior high schools (although exceptions do exist), arrangements can vary widely at the high school level. This is essentially because high school students often have different timetables based on the subjects they take and so having a coordinated lunch program usually just isn’t practical.

However, it is not uncommon for schools without a provided lunch to have an optional bento program that the students pay for and collect at school. This is convenient, but may not be as cheap as if bought elsewhere. For example, at one private high school in Chiba, students may buy bentos on the day as needed (no pre-ordering or advanced payment required), but is considered a little bit expensive at 500 yen (around US$5). At a private high school in Nagano, there is a bento delivery service with the lunches made by those in a cooking stream of a nearby school. As the cooking stream students are training to become chefs, the quality is reportedly very high.

If there is no bento program option, or if students don’t wish to participate, they simply bring their own lunch box from home, buy something at the school shop (if they have one) or alternatively go to the convenience store on their way to school. This last option is quite popular with older students as they often have to leave very early for school and convenience stores are everywhere.

Where the school lunch system exists, however, it is largely a convenient option for many parents and children that teaches many skills around self-organization. Efforts though really should be made to reflect the diversity in today’s schools and make options available for students with special dietary requirements so that they are not excluded.

Here are some more school lunch images to feast your eyes on. Would you like to try Japanese school lunch?

Did you ever have school lunch? What’s the school lunch system like where you live?

Pin me for later

Jessica Korteman is a seasoned travel writer from Melbourne, Australia. She has spent a decade living, working and traveling in Japan, and specializes in Japanese culture, festivals and events, and travel destinations both on and off the beaten path throughout the country.

She is the Founder and Editor of Japanese Food Guide.

Tanner

Monday 28th of November 2022

This has to be one of the most fascinating article I've read today. Makes me kinda hungry looking at all the delicious meals. Thanks for sharing!

Lisa

Tuesday 27th of April 2021

I do admire the system they have at Japanese schools — it's really impressive. I do, however, wish there was a little more leeway when it comes to inclusivity and understanding about dietary requirements. A school I worked at was very accommodating for adults/teachers (especially in regards to milk — it was like an add-on for us) but not so for the kids.

I witnessed more than one incident of a kid not being able to eat his or her yamaimo (a mountain yam that's got a very gooey consistency) and it returning to the plate shortly thereafter. ^^; That was admittedly rare though, and if it came to that point then both teachers and fellow students were very understanding.

Jessica Korteman

Thursday 10th of June 2021

@Lisa, thanks so much for your comment. I agree with you! It's great to encourage kids to try a range of different foods and to finish their plate, and this is mostly a good thing. But I definitely think there should be more autonomy around knowing one's limits and just being able to say, "That's something I really can't stomach."

While it may be rare that a child vomits, they also shouldn't be put in the position that they get sick before they get a pass from their teachers. I think there is enough "peer pressure" to be like everyone else and finish everything in front of them that if the student voices their inability to eat something, they should be allowed to forgo that item. Japanese school lunches have various different components so if they don't eat something like a small side of yamaimo, they are not going to go hungry.