The flowers in shades of red, white and pink can be seen on evergreen bushes and trees in Japan all year, from Aomori prefecture in the north to the Okinawa archipelago in the south. Camellias, which are also called “winter rose” or “Japanese rose”, are considered the oldest ornamental plant in Japan.

For centuries, their seeds have been used to produce oil used for cooking, as well as for hair and skin treatments, and their leaves were made into tea. However, the stubborn conviction of one man on the Goto Islands (五島列島, Gotō-rettō) in Nagasaki prefecture in the south of Japan has led to the creation of yet another way of using camellias for food production: camellia yeast.

Mitsunori Tateishi, the former head of the local chamber of commerce, recalls playing among camellia trees as a child. He enjoyed their smell and used to taste their nectar. While searching for a new way to put the remote Goto Islands, which have been famous for their camellia products for some time, on tourist maps, he remembered his childhood experience. Convinced that the flowers contained yeast, he went to several research institutes to find one willing to help with his quest.

Initially, Tateishi’s idea was met with little enthusiasm. Several research institutes refused to work on it, until he finally found willing collaborators. After many setbacks, they not only discovered camellias did indeed contain yeast, but over the course of ten years, and lots of trial and error, they also managed to use it for making foods and beverages, like rice wine and shochu, fish sauce – and bread!

According to the makers, local food producers have been impressed by its stable fermentation power, and they have been keen to use the special local ingredient to make their products stand out.

Table of Contents

The history of camellias as a food ingredient

Camellia flowers were called “Japanese rose” as early as the 17th century by a German botanist named Engelbert Kaempfer. He stayed in Japan for two years from 1690 and is credited as one of the main scholars to introduce the remote and isolated Japanese island nation to the West – including its flora.

At the time, camellias were widespread in East Asia, but almost unknown in Europe. This changed with scholars like Kaempfer and traders from the Dutch East India Company, who were among the few foreigners able to get limited access to secluded Japan via Dejima, a tiny artificial island in the harbor of Nagasaki.

There are about 250 species of camellia grown around the world today. The Camellia sinensis is typically used for the cultivation of black and green tea, which is made from its leaves and buds. It is originally from India, and from there was brought first to China and thereafter to Japan. While Europe mostly preferred coffee, the English became a country of tea drinkers, and therefore also of camellia cultivators, who sent botanists out into the field to get seedlings and information on the valuable plant.

Apart from tea, another very common use is camellia oil, which is also called “tea seed oil”, made from camellia seeds. Barely known outside of East Asia, some called it the “olive oil of the orient”. It was commonly used for cooking, especially in the south of China, where it was used by millions of people – but in recent years, it has been increasingly replaced by cheaper oils. Camellia oil is made from the seeds of the Camellia oleifera tree, which are pounded to a coarse meal, before they are dry-roasted, steamed and cold-pressed. The process takes a long time, which drives up prices and therefore led to a decline in production.

In Japan, camellia oil (椿油, つばきあぶら, tsubaki abura) pressed from seeds of the Camellia japonica (椿, つばき, tsubaki) has been traditionally used for hair care as well as skin care, with some use also for consumption.

Revitalizing the Goto Islands

The Goto Islands in the south of Japan belong to Nagasaki prefecture. Referred to as Gotō-rettō in Japanese, literally “five-island archipelago”, the five biggest islands are Fukue, Hisaka, Naru, Wakamatsu and Nakadōri. However, the entire archipelago is actually made up of about 150 islands, inhabited by about 50,000 people. It takes 1.5 hours by jetfoil (a type of hydrofoil vessel) and 2.5 hours by ferry from Nagasaki city to the main island of Fukue.

The Goto Islands are among the most rapidly graying areas in the country. Senior citizens make up between 40 and 50 percent of the population on the islands. Up to 90 percent of senior high school graduates leave the islands, most of them never to return, as they go on to university and stay for qualified jobs in the cities.

Despite such issues and their remoteness, the islands have attracted around 1,000 newcomers in the last five years, thanks to their abundant nature, their mild climate and a successful revitalization program called “Goto Smart Island Framework“. It consists of many different cooperation projects between the local governments, academic institutions like the University of Nagasaki, and local companies and service providers.

The goal of the government subsidies is not only to help maintain the local island community, but is also an investment in Japan’s security. The government wants to prevent the island population from shrinking even further, which one day might mean the islands would have to be given up. Their location opposite the Korean peninsula and mainland China makes them a strategically important part of Japanese territory.

The ‘Goto no Tsubaki’ project

People who decide to move to the Goto Islands can expect to receive many types of support in finding accommodation and jobs, as well as subsidies from the government, either directly, or via the support of employment opportunities on the islands.

One such initiative targeted at newcomers (“I-turn”) and returnees (“U-turn”) is Gotō no Tsubaki (Camellias of Goto), a project cultivating camellias on the island for various uses. It was founded in 2018 as a subsidiary of the Japanese company MTG, which creates and markets beauty, health and hygiene brand products. Goto no Tsubaki currently employs nine people, two of whom relocated to the island, according to company president Tomitaka Tanigawa. He himself did a “U-turn”, i.e. he was born on Goto, left for some time, and then returned.

Another returnee is Hayato Imamura. He had left the islands to go to Fukuoka, a major city in the west of Japan, to attend university. Later, he went to Osaka, another metropolis, and lived there for seven years. Turning 30 was also a personal turning point. Every time he went to the island on vacation, he increasingly enjoyed being there. “I came back because of nature,” the 32-year-old said. While there are things one cannot do on the Goto islands, Imamura says that on the islands “entertainment is free”!

Since his return two years ago, Imamura has overseen the camellia garden of Goto no Tsubaki, which spreads over four hectares on the main island, Fukue. As it takes over 20 years until camellia trees grow to a sufficient height, they took over the camellia garden from previous owners. The harvest is done by hand. Outside of harvesting season, the gardeners make sure the trees grow properly and in a controlled way. If they get too tall, it would become too dangerous to pick the petals and leaves, so the growth of the trees is restricted.

The benefits of camellia yeast and camellia yeast products

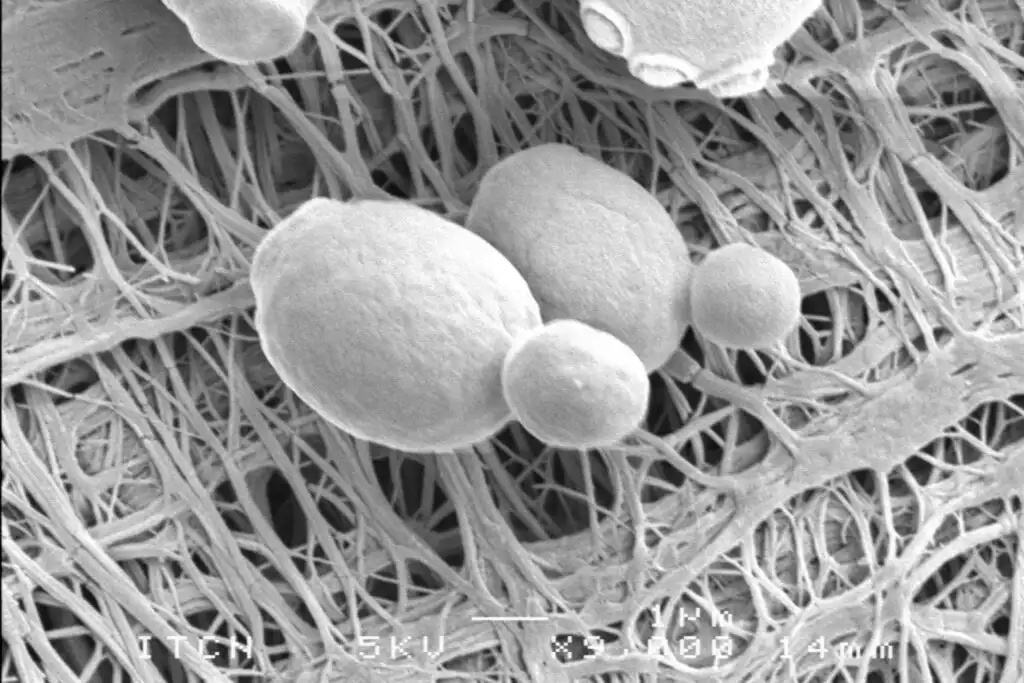

Initially, it was unclear if camellia yeast was usable for food products at all. In the end, it took ten years and several adventurous participants to find out that Goto camellia yeast (五島つばき酵母, ごとうつばきこうぼ, Gotō Tsubaki Kōbo) was indeed not only usable, but thanks to particular characteristics indeed very suitable for food production.

One collaborator was a brewery master who agreed to use it for rice wine (日本酒, にほんしゅ, nihonshu). The first time did not work, but on second try, the camellia yeast rice wine was a success! Within just one week, the special batch was sold out, according to the company.

Goto no Tsubaki went on to test camellia yeast for making wine and shochu (焼酎, しょうちゅう, shōchū), which worked very well.

One of the issues when making distilled alcoholic beverages like shochu is that the resulting taste can vary. With camellia yeast, however, they found that the shochu taste became stable. In fact, a genome analysis confirmed such observations. This helped convince food producers, including a local Italian restaurant, which started using the yeast for its pizza dough.

The locally sourced yeast also solved a separate issue, as at certain times during the COVID-19 pandemic they had found it difficult to procure yeast from abroad. The only downside was the cost at two times the price of artificial yeast. According to Tanigawa, the company currently sells about 500 kilograms of camellia yeast per year to local bread, shochu and wine makers.

When it came to making bread with camellia yeast, Tanigawa said it took them a long time to be successful. Compared to artificial yeast, wild yeast is generally thought to have weaker fermentation capabilities. Wild yeast would make bread turn out harder and less fluffy than artificial yeast. Some people also dislike the smell of wild yeast. However, there were no such issues with camellia yeast, according to the Goto company.

They do not only sell yeast to other companies, but also make products with camellia yeast themselves, like hishio (醬, ひしお), the name of a soy bean paste similar to miso made from koji mold (麹, こうじ, kōji) and salt water. Hishio can also be used to name the watery mash left over from making soy sauce. The golden colored type of hishio with koji has a refreshing scent and light flavor that is said to go well with pasta and meat dishes. The darker type, made with locally sourced fish, is said to go well with egg on rice (卵かけご飯, たまごかけごはん, tamago kake gohan).

The company stresses it only uses locally caught fish like sea bream and flying fish to make the Goto no hishio products. This is not only to do with cost, but also sustainability. In the last two decades, the number of brown algae has gone down significantly due to species like rabbitfish, spiny dogfish, and shellfish feasting on it. This is transforming underwater seaweed forests into marine deserts (isoyake), eventually only populated by sea urchins. Rabbitfish are not yet typically caught for consumption, though scientists at Kindai University in Osaka, for example, are conducting experiments and trial studies to change this.

Goto no Tsubaki also make non-food products from different parts of the camellias, like facial oil, toner and soap.

While the discovery of camellia yeast has been quite the achievement for the Goto no Tsubaki project, their hopes for potential future usage of camellias, of which there are over 4.4 million bushes and trees on the Goto islands according to officials, do not end there.

In February 2021, they found lactic acid bacteria, which strengthens the immune system, in camellia flowers, which were successfully isolated. In order to make use of that, research is continuing in cooperation with local universities and research institutes.

Visit the Goto no Tsubaki Online Shop here: gotonotsubaki.co.jp

Sonja Blaschke is a multilingual freelance print journalist and TV producer from Germany based in Japan since 2005. She reports mostly about social issues and politics in East Asia & Australasia and is the editor-in-chief of a German-language magazine on business in Japan. In 2022 she directed her first TV documentary about young Tokyoites moving to the country to take up rice farming. In her spare time, you are most likely to find her at rock & metal concerts.