Would you pay two hundred dollars or more for one watermelon? And what if I told you after putting down that amount of cash for one piece of fruit, that you couldn’t even eat it?

Yep, Japan is home to the uniquely shaped and inedible Shikaku suika (四角スイカ, しかくすいか) or square watermelon, and if you want one, you’re going to have to be prepared to pay a pretty sum for it.

Japan is well-known for having expensive fruit that is produced largely for the gift market, and square watermelons are no exception. But unlike many other fruits that taste as good as their impeccable presentation, this cube-shaped fruit is for display purposes only.

That’s right, they’re completely ornamental, designed to sit on a shelf and do what exactly?

Let’s dive in and see what Japanese square watermelons are all about.

Table of Contents

What’s the purpose of an inedible watermelon?

Much of the appeal of a square watermelon is indeed adoration of its unique form. The farmers of this special fruit often cite having one to peer upon a way to “blow away the summer heat”.

I guess you can consider it a feast for the eyes and a visual reminder of the satisfying feeling of having your thirst quenched by a sweet and juicy watermelon on a hot summer’s day.

Just as Japan’s summer festivals provide an invigorating atmosphere with lots of food, drink, music and dancing, square watermelons are also said to re-energize and act as a symbol of collective effort to overcome the hottest part of the year. In this regard, having one displayed in public spaces is a way to motivate and thank workers and constituents for making the effort to continue going about their business in the heat, giving them a little something special to smile and fawn over.

While some department stores and luxe fruit shops do sell them to the general public, given the steep price tag, most often they are bought directly by the stores themselves (or by five-star hotels and other upmarket venues) for display in-store only as a kind of marketing tool to sell the opulence of their goods and services, and to get the attention of potential customers. They’ll be given pride of place at an entrance or lobby, or a prominent position within the fruit selection, to not so subtly give a high-end vibe, as well as something fun and interesting for customers to enjoy during the scorching summer.

Of course, while you look at a fruit you’re either unable or probably never going to buy, the hope is that you will buy something else. I mean, most other fresh produce seems cheap in comparison, even if it is generally more expensive than many other countries. If purchased, it is almost always as a very elaborate gift rather than display in one’s own home.

How are customers alerted to the fact square watermelons are not for eating?

Its intention for ornamental use instead of eating is usually indicated on the label. If you look closely at the above example, you can see the term 鑑賞用 in parenthesis, meaning it is “to be appreciated as something of worth”.

More common in this context, however, is the term 観賞用, which is used when enjoying something wonderful with the eyes; for visual appreciation, if you will. Both are pronounced Kanshō-yō.

How were square watermelons invented?

When talking about Japanese square watermelons, we’re almost exclusively referring to “Zentsujisan Shikakusuika” (善通寺産・四角スイカ) or Zentsuji square watermelons.

Zentsuji (善通寺市, Zentsūji-shi) is a charming city of some 34,000 locals in Kagawa Prefecture on Japan’s Shikoku island, along the route of the renowned Shikoku 88 Temple Pilgrimage, where square watermelons have become their signature product. After developing them more than 50 years earlier, Zentsuji’s square watermelons were officially recognized under the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF)’s Geographical Indication (GI) Protection System in 2019.

Although already trademarked, this designation certifies a product’s origin and quality. Other well-known international examples of GeographicaI Indication include Champagne and Darjeeling tea, and acknowledges the important role of physical location, such as soil, water and climate, in the resulting product.

Only the very best square watermelons of the area that fulfil certain quality standards can be shipped as Zentsujisan Shikakusuika. This includes a weight of between 5.5 and 8kg (on average, Zentsuji square watermelons weigh approximately 6 kilograms) and having vertically-aligned stripes on its skin.

Before square watermelons, Zentsuji was already a well-known area for growing watermelons, where the warm climate and low levels of rainfall make it particularly suitable for cultivation of this iconic summer fruit. However, with the increase in availability and variety of other summer treats like ice creams and cold beverages at supermarkets (and later convenience stores) nationwide, the demand for watermelon (and hence sales) declined.

Despite increased competition, the farmers of the area still wanted to grow watermelons and so came the idea of developing a “high value-added” product to add to their offerings. The development of what would later become square watermelons began around 1965, the pioneering of which is credited to a local farmer by the name of Yamashita, whose legacy is still carried on today by his son.

The registered producers’ association spent an entire decade studying and experimenting with different cultivation techniques including containers for molding, and this led to the invention of the first square watermelon around 1975.

These first Japanese square watermelons were originally grown to be edible and the perfect storage solution. Grown into a 18cm square cube, they sit perfectly within the standard shelf height of a Japanese refrigerator, which overall tend to be more petite because of on average smaller living spaces.

Of course there are other advantages to the square shape too, including being easier to stack for transportation and easier to cut without the watermelon rolling around on the cutting board.

Why don’t farmers grow edible square watermelons anymore?

There was, however, one major problem. The cost was simply too high for an item that needed to be consumed within days, the novelty shape barely given due appreciation before the first cut.

If allowed to develop to maturity so that the watermelon is juicy and ripe, it would only have a shelf life of around a week. If you factor in the several days that it takes from harvest to arrive at places of sale, the consumer might only have 2-3 days to eat it. For a product that costs many times that of a regular supermarket watermelon (and tasted the same), it just didn’t provide sufficient value.

In order to prolong its shelf life and improve “cost performance,” square watermelons evolved into an ornamental fruit exclusively for display and the gift market. Picked from the vine while still unripe, it can keep for a much more economical six months, allowing one to show it off as a status symbol for up to half the year.

While technically you can still eat a square watermelon, you really wouldn’t want to. If you could bring yourself to cut one open, you’d find bland, yellow flesh and none of the signature sweetness you’d typically find in a regular Japanese watermelon.

How are square watermelons grown?

The concept of growing a square watermelon is relatively simple. Essentially while the watermelon is still growing on the vine, it is placed into a transparent box that is smaller than the watermelon’s matured size, making the watermelon mold into a square shape. That’s right, it’s not a special seed variety or genetically modified as some people are led to believe, it’s actually a regular round watermelon manipulated into a new shape.

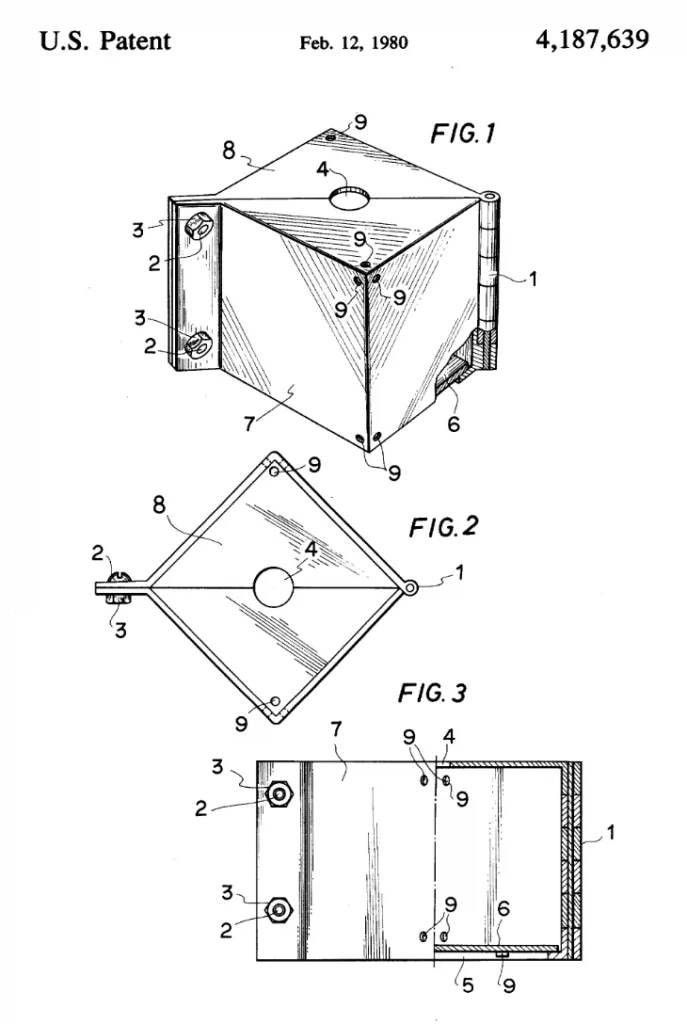

An application to patent a box used for the “molding process for a natural fruit of a fruit-tree or vegetable” with specific reference to “melons” was filed by Japanese graphic artist Tomoyuki Ono in 1977. He created quite the splash when he showcased his square watermelons at a gallery in Ginza, Tokyo, and hence is often credited with inventing the square watermelon itself, despite Zentsuji’s efforts pre-dating the exhibition.

The patent for his box design was approved in Japan in 1978 and a subsequent filing for a US patent was also approved in 1980 (both of which have seemingly expired). An application for a patent on a “square watermelon mold” was also applied for by the Ningxia Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences in China and subsequently granted in 2013, the legal status of which also appears to be expired.

Basically all box designs for growing square watermelons follow the same principle. They have transparent sides for easy checking and to let sufficient light through for development of the signature color pattern, a hole in the top to accommodate the stem, a sturdy metal frame that keeps a solid shape and stops the watermelon from busting through it as it grows, and is designed to be able to be assembled and disassembled panel by panel around the watermelon so as to prevent damage to it. This last point is of particular importance when selling a premium product designed for its aesthetic value.

The boxes used for Zentsuji square watermelons have an iron frame and create an end product of precisely 18cm x 18cm, as this conforms to standard shelving heights in Japanese refrigerators.

Zentsuji farmers use a large watermelon variety called “Shimaō” (縞王, しまおう) or “Stripe King” for its deep-green, almost black, variegation that creates the impressive vertical stripes of the area’s signature product. Similar varieties that can mimic this effect, however, are also permitted under Zentsuji’s Geographical Indication.

When the watermelons reach a suitable size, only the best ones are chosen to be placed inside the boxes. From the time the watermelon is placed inside the box to the time it is harvested, is a period of only 10 days. It is cut from the vine while still unripe and the box dismantled carefully around it by unbolting each side.

Why square watermelons are so expensive

It might sound simple (and fast) enough to grow a square watermelon, but a lot can go wrong during this process, including damage, disease, unfavorable weather conditions and un-aesthetically pleasing results, rendering them either unsuitable for sale as Zentsujisan Shikakusuika or for sale at all.

Great care must be taken to ensure the watermelon does not get scratched. Even a very small scratch at the time of placement inside the box will double or triple in size by the time it fills it.

The watermelon also needs to fill the box evenly on all sides and the stripes must all be in near perfect vertical alignment. A square watermelon with stripes on an angle won’t make the grade as Zentsujisan Shikakusuika. This means that placement and balance are critical to ensure it grows to these ideal aesthetics. That’s why you’ll see Zentsuji farmers placing their square watermelons on a solid base with wooden planks for stabilization.

Zentsuji square watermelon farmers check on each one 2-3 times a day to assess their growth status and condition. They have even been known to put hats on them when necessary to try to negate the heat, as unseasonably hot weather conditions can cause much of the crop to fail. These frequent checks are also paramount to ensure precise timing of cutting from the vine. If they are allowed to mature too long, they lose their shelf-life and hence market value.

Today only seven producers remain due to a lack of successors, with a combined annual harvest of around two-hundred Zentsujisan Shikakusuika. In bad years, the yield can be as low as seventy, which drives up market price even further.

Once harvested, the square watermelons are taken to a cooperative warehouse for packaging and distribution, typically starting at the end of June through to the end of July. They are packed by the farmers themselves, who are all seniors. A trademarked sticker that denotes the watermelon as an official Zentsujisan Shikakusuika is placed onto each one and packed in its own individual box, designed to fit the 18cm square watermelon perfectly.

The square watermelon comes with its own cushion (that can be used by the purchaser to display it) and is surrounded by soft packing material to protect it. Before the box is sealed up, a guide for decorating it with a ribbon is enclosed. When finished, it looks like a bow with a sticker backing that you might find on a birthday present with ribbon tied around its circumference and two pieces (sometimes curled) arranged on either side of the sticker.

So just how much do square watermelons cost?

A square watermelon in Japan will set you back a minimum of 10,000 yen (or very roughly US$100). In a big city like Tokyo, you can expect to pay 20,000 yen (US$200) or even more.

It’s not uncommon to find ones that cost upwards of 50,000 yen ($500), especially in years when the yield hasn’t been high.

Zentsujisan Shikakusuika that are shipped internationally can be sold for an incredible 80,000 yen ($800) plus.

Have you ever seen a Japanese square watermelon in person? Would you ever consider buying one?

Read more:

Check out Japan’s watermelon piñata, a game that is sure to liven up any summertime gathering!

Pin me for later

Jessica Korteman is a seasoned travel writer from Melbourne, Australia. She has spent a decade living, working and traveling in Japan, and specializes in Japanese culture, festivals and events, and travel destinations both on and off the beaten path throughout the country.

She is the Founder and Editor of Japanese Food Guide.

Angie Meloy

Sunday 16th of July 2023

I was in Japan in 1977 and we saw these in department stores (where gourmet foods are often sold.) At that time, they were a new novelty and were edible. It was explained to us how they were formed and that people were giving them as gifts, especially to someone in the hospital. We were very intrigued! I wish I could remember their cost at that time.

Alice Gordenker

Thursday 11th of August 2022

I didn't know they weren't for eating!!

Jessica Korteman

Tuesday 16th of August 2022

Isn't it fascinating? Definitely a different way of looking at fruit as gifts!