Inarizushi, deep-fried tofu pockets (Aburaage) cooked in a sweet broth and stuffed with vinegared short-grain rice, is a common type of sushi that has been attracting Japanese people since the Edo period.

Inarizushi (稲荷寿司, いなり寿司, いなりずし), otherwise known as Inari Sushi, is a staple food in Japan, where you won’t have trouble finding it at convenience stores right next to the Onigiri. You sometimes see Inarizushi and Makizushi (sushi rolls) packaged together. This is known as Sukeroku (助六, すけろく), a pun on the same title played in Kabuki theater.

In English, this dish is commonly referred to as ‘Inari Sushi’, however it is not pronounced this way in Japanese, where the ‘s’ sound often changes to a ‘z’ in compound words. In Japan, however, you may come across Inarizushi being referred to as Oinarisan. Both are in reference to the deity O-Inari, who, among other things, is the Shinto god (kami) of rice.

White foxes are said to be the messengers of O-Inari and according to Japanese folklore, deep-fried tofu or Aburaage is a fox’s favorite food, and therefore makes the perfect name for a dish that features both ingredients. When in the Kansai region, however, the term Age-zushi is more commonly used, while elder Japanese may call it Shinoda-zushi, which comes from a local dialect.

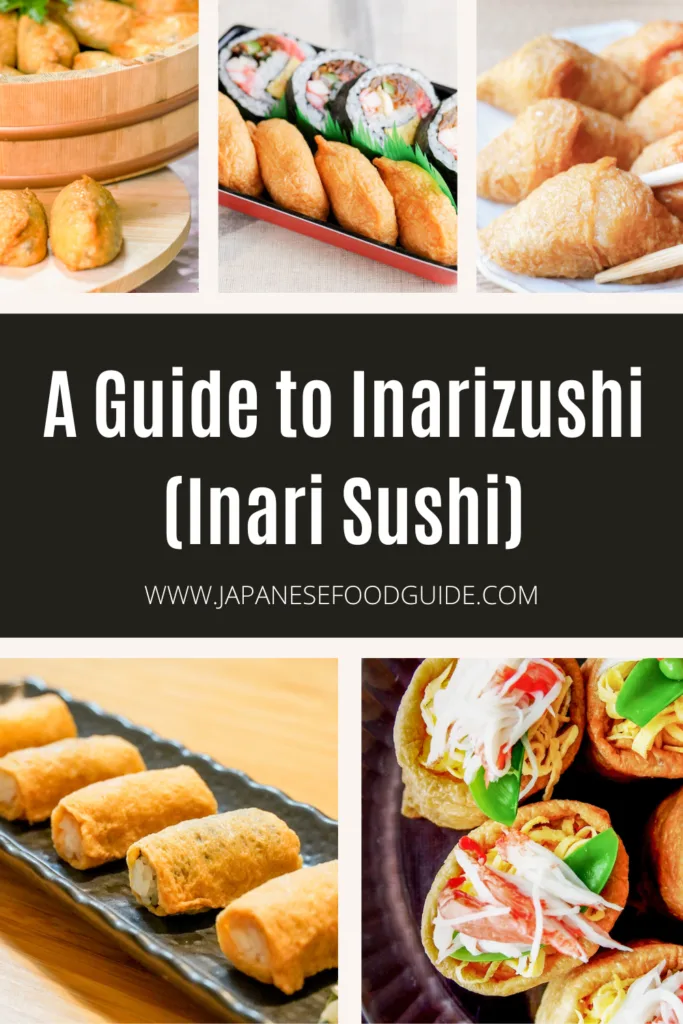

There are also several varieties and shapes of Inarizushi depending on the region. These days, we have unique versions of Inarizushi as well. As a qualified Inarizushi Meister from the Japan Inarizushi Association, let me share with you everything you need to know about this popular sushi dish.

Table of Contents

Origins of Inarizushi

In 1837, in the latter part of the Edo period, writer Morisada Kitagawa published a 35-volume illustrated encyclopaedic series entitled ‘Morisada Mankō’ (“Morisada’s Sketches”) that documented Edo-era culture. It took him nearly 30 years to complete the series and in it he mentions that Inarizushi originally started in the Owari district in Nagoya and became popular during the Edo period.

Fifteen years later, in 1852, a drawing of Inarizushi being sold by a merchant appeared in Kinsei Akinaizukushi Kyōkaawase, a book by the late-Edo era anthropologist Ishizuka Hōkaishi documenting the song-like lyrical calls used by the merchants to sell their products. The image included a price list and stated that the price of 1 piece of Inarizushi was 16 mon (1 mon was the equivalent of about 30 yen), making it 480 yen in today’s currency (about US$4).

While it might sound expensive, it was served in a very long Shōdenzushi style (more on that later) equating to approximately 3-4 pieces of today’s Inarizushi, and was the same price as a bowl of soba or udon. A half-size portion was 8 mon (240 yen) and 1 bite was 4 mon (120 yen). It was presumably fast food for men who worked in Central Edo (now Tokyo) for Sankin Kōtai (alternate attendance) duty, a policy of the Tokugawa shogunate of the time to maintain control over the country’s feudal lords by requiring them to alternate spending a year in their domains and a year in the capital.

Back in the Edo period, people enjoyed Edomae-zushi, Inarizushi and Makizushi, but Edomae-zushi (the nigiri-style sushi topped with fresh seafood from Tokyo Bay) was relatively expensive in comparison to the cheaper Inarizushi and it surged in popularity after Edomae-zushi was banned during the controversial Tenpō Reforms, which saw the prohibition of various “luxury” goods.

Although many Inari Sushi chefs existed, a man known by the name “Jyukkendana Jiroko” who had a store called ‘Inariya’ in Jyukkendana in the Nihonbashi area of Tokyo, was the most famous. Well-known for his witty chatter, he sold an incredible 10,000 pieces a day, and apparently once even fulfilled a special order of 30,000 pieces. Jiroko’s Inari Sushi used okara as the filling instead of rice (‘okara’ being soy pulp, or the insoluble parts of the soybean that remain after filtering during soy milk and tofu production), although he may have had rice on offer as well.

Samurais from rural areas who worked for the feudal lords and were also in Edo (Tokyo) for Sankin Kōtai duty are said to have loved Inarizushi so much that they brought back the recipe to their various domains, and it subsequently became popular nationwide.

Regional variations of Inari Sushi

Just like the mochi used in New Year Ozōni soup, the basic styles of Inarizushi are divided into two major shapes: the round, barrel-like shape (known as Tawara) used in East Japan or Kanto (such as Tokyo), and the triangle shape (Sankaku) that is dominant in West Japan or Kansai (for example, Osaka and Kyoto).

We can also see the difference between the regions in the appearance and taste of the Aburaage, and the ingredients put inside. In the Kanto region, you’ll likely find a sweet-salty combination (甘じょっぱい, amajoppai) that gives a punchier taste, whereas in the Kansai region they prefer using dashi broth more, often a combination of dashi, sugar, soy sauce and starch syrup. The color of the Aburaage is also darker in the Kanto area from using Koikuchi soy sauce versus in the Kansai area where they use a light-colored Usukuchi soy sauce.

Kuro-Inari or Black Inarizushi also exists and is a famous dish of Tsuwano-chō in Kanoashi district, Shimane prefecture, where the Aburaage is cooked in brown sugar (kurozatō). However, you can also find it in other areas of Japan, including at the Edo period restaurant Yaozen in Yokohama (formerly in Kamakura and way back in the Edo period in Tokyo’s Asakusa district).

While Yaozen uses brown sugar, other establishments may use soy sauce instead, in which they use a process called Tsugitashi, a term that refers to continuous adding of a condiment (in this case soy sauce) from the same container whenever the desired amount of sauce decreases. Through both of these methods, the Aburaage caramelizes resulting in a dark, almost black color.

As for the filling, East Japan tends to prefer using vinegared white rice, while West Japan opts for Gomoku-meshi, a mixed rice that includes cooked mushroom and other vegetables like carrots.

There are other regional exceptions too, such as in Aomori prefecture, where they put red mochi rice inside. In Ibaraki prefecture, there is Soba Inari that is stuffed with soba noodles instead of rice, and Konnyaku Inari can be seen in Gifu and Kochi prefectures that uses konnyaku seaweed instead of Aburaage as the outer layer.

Even though Saga prefecture is located in the South-west, they tend to have vinegared white rice like in the East, rather than mixed rices, such as Gomoku-meshi or Chirashi-zushi.

Just like many other dishes in these modern-times, however, regionality is becoming increasingly less defined as premium local ingredients are more readily available in popular stores, restaurants and even at convenience stores, especially in larger cities. You can therefore find some regional types of Inari Sushi outside of their areas of origin, such as premium Nankan-age from Kumamoto in popular stores in Tokyo.

Types of Inari Sushi by shape, style and ingredients

1. Barrel shape (Tawara)

Typically seen in East Japan, such as Tokyo, this round, barrel shape, referred to as ‘tawara’ in Japanese, is the standard style of Inarizushi.

2. Triangle shape (Sankaku)

The triangle shape is essentially Kansai style. You will see this style in convenience stores all over Japan, but it is generally more common in West Japan, such as Osaka and Kyoto. It looks like fox ears, an ode to the dish’s namesake.

Typically, it’s made using dashi from kelp, bonito and donko (expensive dried shiitake mushroom), along with sugar, soy sauce and salt. However, Kyoto style is more of a plain dashi taste.

3. Long shape (Shōdenzushi)

Shōdenzushi is a very old long style of Inari Sushi using dashi from kelp and bonito, and adding sugar, soy sauce and starch syrup.

It’s a specialty of several stores nearby Menuma Shōdenzan temple in Kumagaya city, Saitama prefecture, and is similar in style to what was served during the Edo period when Inari Sushi originated.

4. Open type

For those who think Inarizushi is too sweet, this version might help. Although the pouch is typically made with dashi, soy sauce and sugar, and hence retains a sweetness to the outer layer, this open type allows for very creative versions with unorthodox ingredients tucked inside that can work well to cut through and balance the sweetness.

The version depicted above uses thinly sliced strips of egg, snap peas and shredded crab. However, you can experiment with any combination you like. Seafood, salad and vegetables are common for this style.

5. Roll type

This type uses Kumamoto’s famous Nankan-age, a local specialty version of Aburaage from the town of Nankan. Notoriously very difficult to handle, Nankan-age cannot be shaped into a pouch and is therefore wrapped up into a roll instead. Even removing the oil takes a couple of hours in preparation, but it is chewy and very delicious, making it worth the effort.

It is typically cooked with dashi (kelp, bonito and premium dried shiitake mushroom), soy sauce, sugar and starch syrup.

6. Dashi Inari type

The restaurant Kaiboku in Nihonbashi (Tokyo) has been the leader in this style. As the name suggests, dashi broth is the star ingredient, resulting in a juicy and delicious end-product.

How to make Inarizushi・Inari Sushi Recipe

Pro tip: To make Inari Sushi, be sure to buy Aburaage that is made for Inarizushi (if you buy the regular Aburaage, it will be difficult to open up and put rice inside).

This is the recipe I make.

Ingredients for Inarizushi:

10 x Inarizushi Aburaage (deep fried thin tofu bags)

1.5 cups of dashi soup

5 tbsp sugar

3 tbsp soy sauce

1 tbsp mirin

Boiling water

Ingredients for sushi rice:

3 gō of Japanese short-grain rice (that is about 2.7 cups of rice in Japan)

Sushi vinegar (mix of 4 tbsp rice vinegar / 3 tbsp sugar / 0.5 tbsp salt)

Method:

1. Cut the Aburaage in half (making 20 pcs). Then use a rolling pin to flatten them (this makes opening the pouches easier) before gently opening them. This process can take some time, but is an important step as it’s actually quite difficult to open the Aburaage like a pouch if you don’t roll them enough.

2. Put the cut and opened Aburaage into hot boiling water for a minute to remove excess oil.

3. Remove them from the boiling water and cook the Aburaage in the dashi soup, sugar, soy sauce and mirin.

4. Once the rice is cooked, pour the sushi vinegar over it immediately. Use a fan to cool it off and mix it well. Leave it until it gets drier and then stuff into the Aburaage pouches.

If you don’t have the time or inclination to make Inari Sushi from scratch, you can make a super easy version using sushi vinegar (the already-made combination of vinegar, sugar and salt) or use chirashi-zushi mix and mix with cooked rice. Then stuff the rice into already cooked Aburaage for Inarizushi.

Where to buy Inarizushi

If you are reluctant to make it on your own, a simple visit to any nearby convenience store in Japan (and many supermarkets too) will yield results. Sometimes you will find interesting ones there, like Maitake Inari (using Maitake mushroom) at Seven Eleven and Yuzu Inarizushi at FamilyMart.

Here is a Google map link detailing some of the best Inari Sushi shops and restaurants in Japan. On the list, you can find some of my faves, such as Ginza Platinumya next to Kabuki-za in Ginza, Tokyo.

Have you ever tried Inarizushi? What’s your favorite version of Inari Sushi?

Pin me for later

Kyoko Nagano is a serial entrepreneur and Michelin star restaurant enthusiast based in Kanagawa. As a Certified sake sommelier, fermented food sommelier, and tofu, inarizushi and soy oil meister, she is an expert on Japanese food and drink.

Kyoko has spent 17 years abroad in 4 countries, and is now on a mission in Japan to support small craft sake breweries and traditional cultural businesses to help them survive.

Kaori

Tuesday 27th of September 2022

Love that you included a recipe!