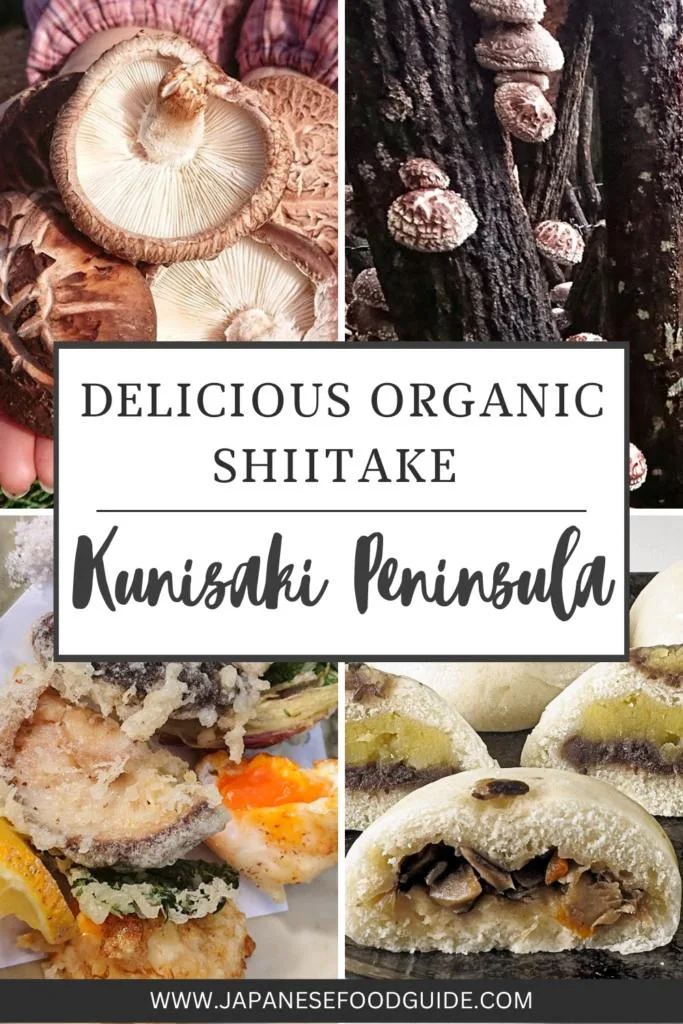

The Kunisaki Peninsula is located on the north-eastern side of Oita prefecture in Kyushu, facing out towards the Seto Inland Sea. The rhythm of life moves in tandem with the changing seasons in this rural region, which is the leading center for the cultivation of organic shiitake mushrooms (椎茸, しいたけ) in sawtooth oak tree logs.

Fragrant and firm, shiitake are thought to have arrived in Japan from China in the ninth century and are frequently used in both fresh and dried form in Japanese cuisine. Dried shiitake add a richness to soups, stir-fries and stews with their umami flavor. Originally coined in 1908 by a Japanese chemist, Kikunae Ikeda, the term umami means “a pleasant savory taste,” and it is now recognized along with sweet, sour, salty and bitter as one of the five major tastes.

Table of Contents

A return to shiitake mushroom farming roots

Brothers Takafumi and Kenji Kiyosue are third-generation shiitake farmers in Kunisaki, where they work alongside father Yoshiharu and mother Asako in the family business, Kiyosue Nouen. A former salaried worker, Takafumi returned to the farm 10 years ago to help his parents, followed by younger brother Kenji, who quit his job as a chef six years ago.

“I’d been working from morning till night, and it was normal not to see my children at all on some days. It was at this point that I made up my mind to join the family business, following an invitation from my brother,” Kenji says. The resulting change in lifestyle has been a positive one for his family, leading to greater opportunities to spend time with his children, now ages 15, 12 and six.

Many of Japan’s agricultural regions are faced with the twin problems of a graying population and fewer young people willing to take up the farm work mantle, with the average age of shiitake famers on the Kunisaki Peninsula around seventy. Against this background, the participation of younger people like the Kiyosue brothers is vital for securing the future of traditional farming methods.

“Shiitake farming is hard work. Handling the thick, heavy logs puts a strain on the legs and back. And since the shiitake are basically grown in the open, they are affected by sudden changes in temperature and weather,” explains Takafumi.

In recent years, output has been declining due to climate change, with high summer temperatures causing damage to the trees, and warm winters resulting in a lower harvest in the spring. Moreover, spikes in temperature cause the mushrooms to grow too fast, resulting in thin edges which crack easily, and subsequently lower prices. A further challenge is presented by the availability of inexpensive shiitake imported from China.

On the other hand, however, a rising interest in organic food and the farm-to-table concept means that more people want to know where their food comes from and how it was grown. Since the Kiyosue Nouen’s shiitake are produced without the use of pesticides or other chemicals, they dovetail perfectly with this trend.

The Kunisaki Peninsula’s agricultural heritage

In 2013 the Kunisaki Peninsula was officially named as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS) by the United Nations, in recognition of its traditional farming culture and diverse ecosystems. Featuring rugged mountain ranges and deep valleys, the dynamic landscape is beautiful yet difficult to farm, with scant rain and volcanic soil which quickly absorbs any rainfall.

To combat this, over the centuries a linked network of around 1200 small reservoirs was developed to serve as irrigation for the region’s agricultural land, including rice fields and sawtooth oak forests. It is thought that Oita’s shiitake farming began in the 1600s, when shiitake were found growing naturally in the oak logs, and today the prefecture produces around 43% of Japan’s log-cultivated shiitake.

Not only do logs from sawtooth oaks make the ideal incubators for growing shiitake, but having served their purpose, these logs can be returned to the forest floor, becoming part of the environment for the next generation of trees. Moreover, sawtooth oak stumps have the ability to regenerate, and are ready to host shiitake again after about 15 years.

Shiitake season by season

The shiitake mushroom cultivation process takes patience and time. Holes are drilled into the logs and “sewn” with mycelium—the thread-like structure which makes up the body of a fungus. The logs are then left to rest for one to two years until the mycelium’s enzymes have spread throughout the logs. They are next moved to a sheltered cultivation site in autumn, before the shiitake emerge the following spring to be harvested.

Spring is a busy season for the Kiyosue family, who sell their shiitake in fresh and dried forms. In addition to sewing and harvesting in the spring, they must also sort and ship the dried shiitake. In comparison, summer is a relatively quiet season in the shiitake cycle, so the brothers generally fill their time with cultivating rice and pruning the sawtooth oak forest on their land.

With the coming of autumn, they bring in the logs from the previous season to carefully watch over the final months of the shiitakes’ journey to maturity, and fell new logs for the next generation of mushrooms. In winter they cut and drill these new logs, while carefully protecting the incubating shiitake from inclement weather in anticipation of the spring harvest. And so the cycle continues, year in and year out.

Regional shiitake dishes

Despite the uncertainty that comes with working in partnership with Mother Nature, the Kiyosue brothers are committed to bringing top-quality shiitake to customers. “It’s very rewarding when people tell us how much they enjoy our products,” says Takafumi.

Kenji recommends shiitake omusubi (おむすび, rice balls), which were recently introduced on Japanese national TV. The dish consists of shiitake, gobō (牛蒡, ごぼう, burdock root), carrots and abura-age (油揚げ, あぶらあげ, deep-fried tofu), which are sautéed with seasonings and cooked with rice, before being shaped into triangular musubi. “It’s a taste of the Oita countryside, and it’s delicious hot or cold,” he says.

Both brothers also enjoy their mother’s innovative shiitake recipes, including her signature shiitake manjū (饅頭, まんじゅう, steamed buns). These savory treats are made from shiitake and other home-grown vegetables, seasoned with a sweet and spicy sauce and wrapped in a fluffy steamed bun.

Incidentally, neither of the brothers were fond of shiitake as children, but have since grown to appreciate the aromatic mushrooms which now sustain their family. “We can probably say they taste better when you have put in the time and effort to grow them yourself!” Kenji adds with a smile.

Kiyosue Nouen do not currently export their products, but customers in Japan can purchase them here (Japanese):

https://poke-m.com/producers/279978

For Asako Kiyosue’s shiitake manjū (Japanese):

https://kunisaki-tuuhan.com/item-detail/1000307

For information on visiting the Kunisaki Peninsula region:

https://www.millennium-roman.jp/english/

(Scroll to the ‘Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems’ section for details on agricultural experiences, including Kiyosue Nouen, or see this downloadable PDF).

Pin me for later

Originally from New Zealand, Louise George Kittaka is a bilingual writer, content developer and university lecturer based in Tokyo. She writes for a wide variety of media on topics of interest to the international community, including travel, education, business and sustainability.

When she isn’t at her computer, Louise loves exploring waterfalls and going to cake buffets.

Jenni

Monday 6th of March 2023

Kunisaki is a wonderful place and I'd love to try some of those shiitake!

Jenni

Tuesday 7th of March 2023

@Louise, It's great and I hope to go back someday soon and eat more!

Louise

Monday 6th of March 2023

@Jenni, thanks for commenting! The whole region is full of friendly, down-to-earth people. I'm glad you enjoyed it, too.